Beauty in our roots: My journey to animal welfare and humane education

July 21st, 2021

By Helia Zarkhosh, RedRover Communications Coordinator

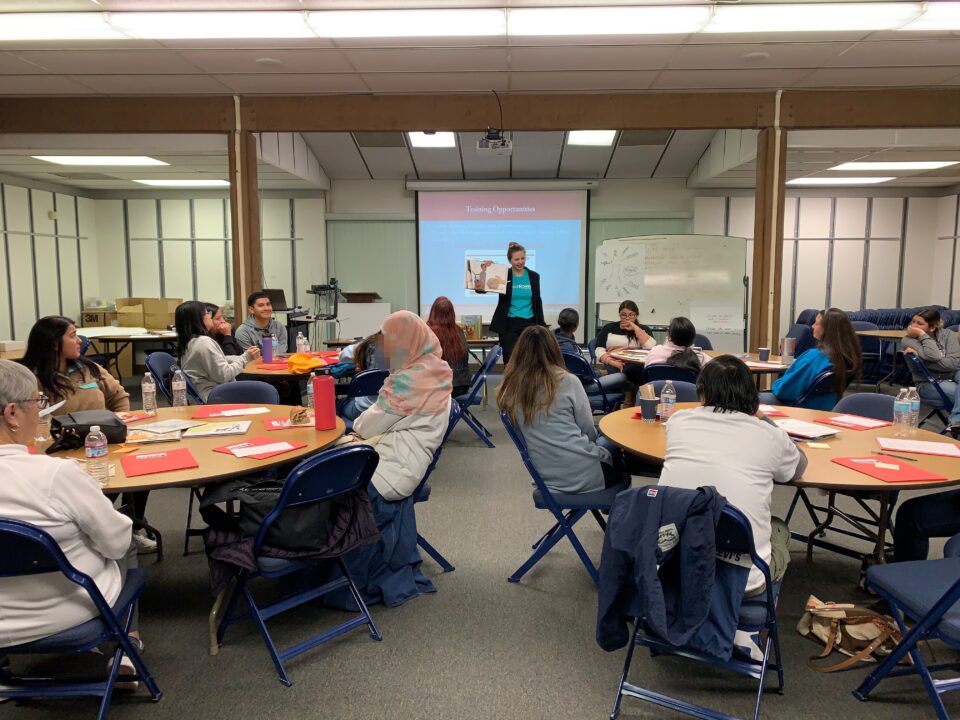

In the latest edition of our “Behind the Scenes at RedRover” series, RedRover Program Coordinator Minhhan Lam shares her journey to working in humane education.

“There is beauty in our roots. Sometimes we think our roots are shameful, and people tell you that you’re not good, or your ancestors are no good or that you come from a neighborhood of no hope and terrible crime. But it’s about the beauty of those places, and I carry that with me.”

– Luis Alberto Urrea

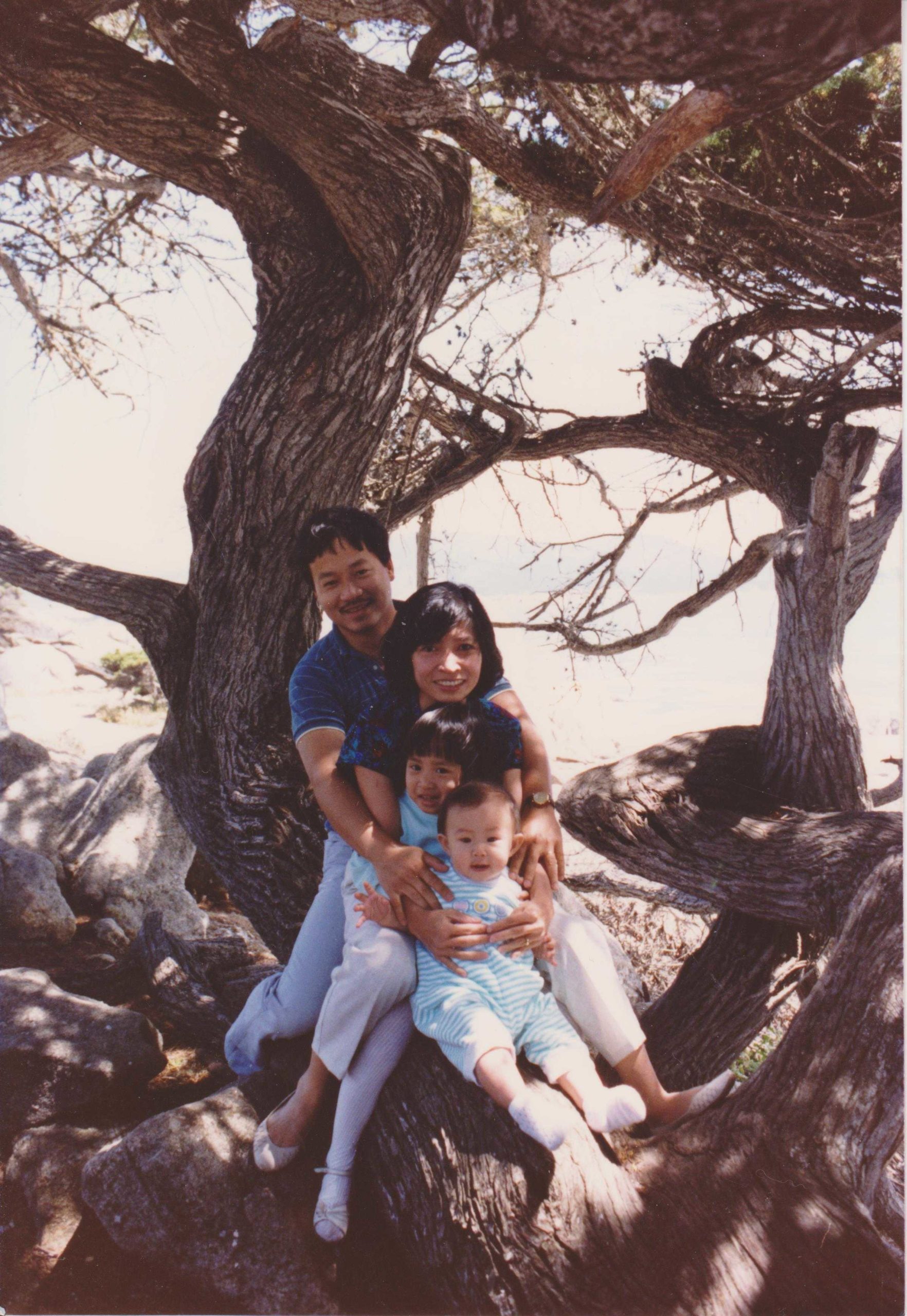

Minhhan with her family

At the height of racial tensions last summer, RedRover staff and our organization as a whole began to examine and reflect on the ways we can better embody racial equity and justice. For one staff member, it became apparent that the skills she’s developed through her role supporting our RedRover Readers curriculum and Kind News magazine content have provided her with the tools she needed to begin to process her own racial trauma, reflect on her upbringing as a child of immigrants, and examine the role she hopes to play in teaching and encouraging children to use their voice to stand up for what they believe in.

RedRover Program Coordinator Minhhan Lam shares, “I self-identify as Vietnamese-American. I am the daughter of immigrants. Growing up, I was fortunate to be surrounded by pets, and I dreamed of becoming a veterinarian. Now, after years of working in the animal welfare field, I feel a calling not only to help animals, but to spread awareness and empathy through humane education.”

Having fled their home as refugees after the fall of Saigon in 1975, Minhhan’s parents eventually established themselves in Sacramento, California, where they raised Minhhan and her older sister. Growing up in an Asian household in America brought its own unique circumstances and experiences. Minhhan remembers an early awareness of being “other” in this country. As a child, she would complain about being made to learn Vietnamese, saying things like, “I’m in America, I have to speak English in order to assimilate!” While she is grateful to have learned the language as part of feeling connected to her heritage, she recognizes that yearning to assimilate was rooted in fear of being an outsider, which she sees as an early sign of intergenerational trauma that was passed down from her parents to her, and even from her grandparents to her parents.

A major cultural difference Minhhan also noticed early on was her parent’s relationship towards animals, including the family’s pets, versus what Minhhan was seeing as the “norm” in other families around her:

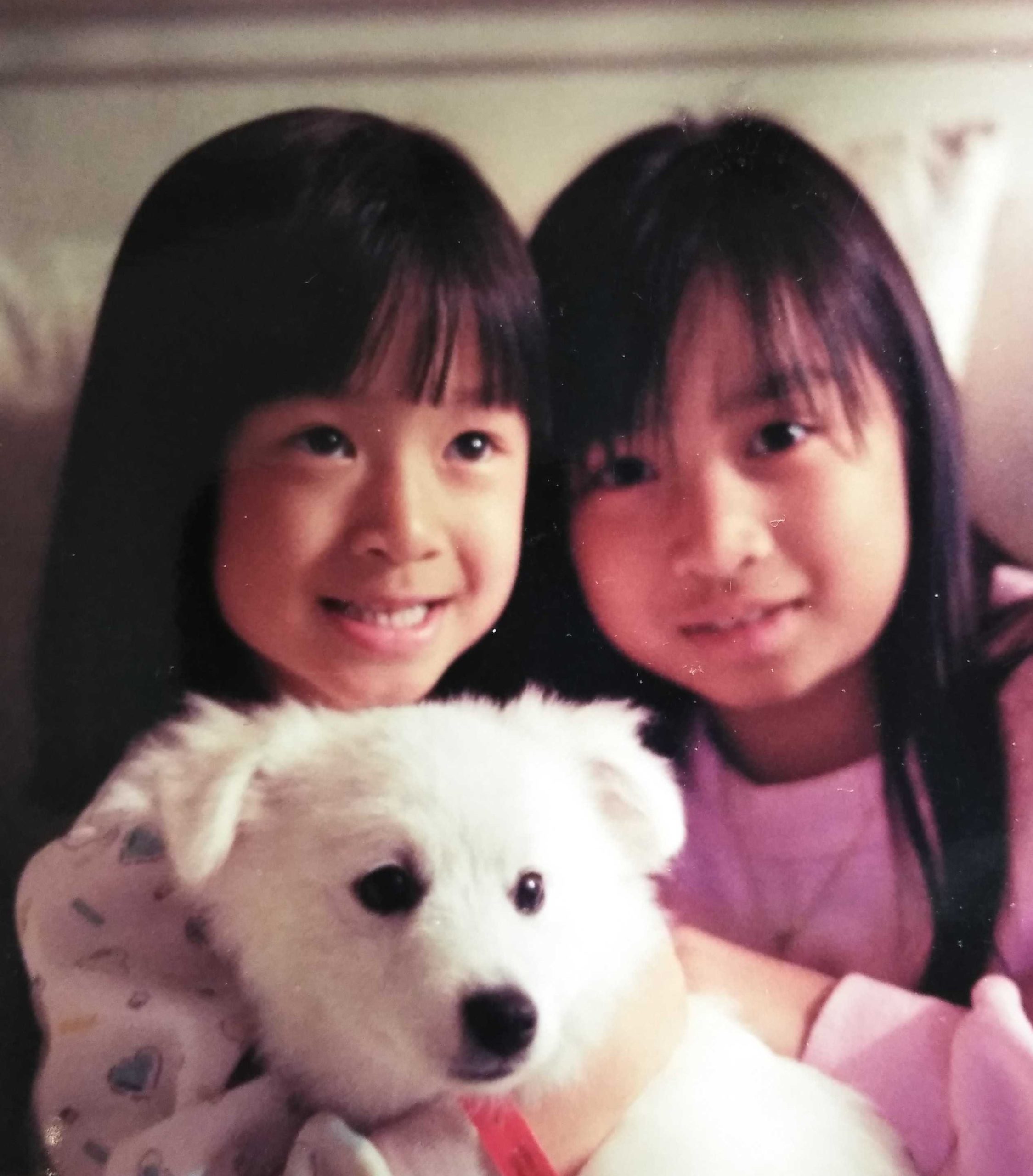

“I was fortunate to have parents who also love animals, but they did so differently than me. I know my dad had dogs growing up, but they were kept outside and watched over the house, and that was a common thing at the time. His family played with them and fed them, but the dogs didn’t step foot inside. And that approach was passed down to my dad. So while I grew up with pets, including dogs and rabbits, they weren’t allowed in the house. I didn’t know any better at the time and I don’t think my parents did either.”

Because she was introduced to animals as a child, Minhhan knew she wanted to be a veterinarian even before she learned the word for the career. She pursued animal science, animal welfare, and ethics courses at the first opportunity. What she learned in these courses – and with further exposure to cultures outside her own – shifted Minhhan’s perspective, and she reflects now that it led her to become more judgmental of her parents not allowing their pets inside the home.

Minhhan with her sister and their first dog, Puffy

This sense of judgment stands out to Minhhan, because it’s exactly what we avoid in all our RedRover program initiatives, especially in our classroom-based curriculum for children through the RedRover Readers program. Without the tools she needed to create a dialogue with her parents around the topic, she felt her only option was to stay silent. She says,

“It’s important to note that I didn’t speak up about my opinions or feelings. I didn’t try to educate my father because it was inculturated that it simply wasn’t my place as his youngest child. It would have been considered so disrespectful to tell him I felt he was doing something wrong. At the time, I thought to myself, ‘Who am I to bring this to him?’

As a child, I carried so much shame when my friends would ask, ‘Why can’t your dog come into the house?’ I think over time, my parents began to feel shame, too, as they became more familiar with American culture. But it manifested differently for them than it did for me because they grew up with different cultural values than I did growing up here. It’s not that my parents didn’t love the animals. They did – but it was going to look different for them than it would for me or you, or people of different cultural backgrounds.”

As a student and now a professional in this field, Minhhan sees this lack of cultural awareness and understanding as a major blindspot within humane education, and one that even our own programs are coming to terms with and addressing through our DEI training. RedRover staff continue to examine the ways in which our programs can help to build a more empathetic society for all while examining and addressing the structural inequities that have contributed to historically marginalized people being underrepresented and underserved within the animal welfare sector. And this work is hard. But we believe strongly that it’s not only worth it, it’s essential:

“It’s important to address the lack of diversity in the animal welfare industry and that I have felt it for as long as I’ve been old enough to work and pursue my career. I recognize these blind spots and disparities and I want to address them, but there’s also a strategy to that. Everybody is in a different place on this journey and I can’t rush it even though sometimes I feel like I’ve hit another wall. I just tell myself to take a few steps back because the other person isn’t ready yet.

We’re now having these conversations that are so hard, but are so important. Because if we aren’t vocalizing our concerns and come in with judgment about different lifestyles or cultures, you’re already losing the very people you’re trying to reach. We all have biases. I do, and it showed when I was judging my parents, even if I didn’t say it out loud. Instead, you have to approach people in the way our programs were designed, through a welcoming-in instead of pushing-out, without bias.”

Now well-versed in this perspective, Minhhan is taking personal inventory as she reflects on her upbringing:

“I’m doing the work and asking myself these questions about where I come from, what are my roots, what are my parents’ roots, how are they different… asking above-ground/below-ground questions like, ‘How are you feeling? What do you think? Why?’ This is how we approach topics in the Readers and Kind News magazine programs. It’s why we communicate the way we do. It’s important that we don’t come in blazing and telling or making ‘should’ or ‘should not’ statements because the moment you do that, you shut the door. You’re not creating a dialogue. You’re creating a monologue. I didn’t realize that before.”

Minhhan with her dog Shizu

Reflecting on her own experience as a child of immigrants in America and the nuances of the discrimination and racism she’s faced as an Asian-American has been both freeing and challenging. During one particularly difficult time of reflection, Minhhan felt like she was losing herself:

“I was in a really dark place and I felt like my light was disappearing. On the Friday of that week, I got on the phone with one of our donors, Deb Congdon, who is just the sweetest. She told me, ‘Don’t give up.’ That simple phrase reminded me that light exists, just as much as the darkness; one can’t exist without the other. But you can choose how much light or darkness you let into your life. Set healthy boundaries, rest, rejuvenate, and stay strong in spite of it all. There is strength in community, in solidarity, in accountability, in honesty. Remember that you are your own best advocate, but you don’t have to take on the world by storm on your own. Look around – you’re not alone. Don’t give up.

Deb re-sparked what I thought I had lost inside of me. That genuine love and care that I have for animals, and the hope that I want to instill in children across the nation and world…I’m here because I believe in that lasting change and that’s what I fall back on. It’s so easy for me to let myself spiral if I can’t see past ‘Why am I doing what I’m doing?’ But I genuinely want to make a difference.

This work that I’m doing at RedRover informs how I approach myself, and with these tools that I’ve learned from the RedRover Readers program and from writing, editing, and coordinating a children’s magazine, being trained to think through a humane educator lens, it means maybe before I jump to conclusions or to an emotional reaction, I’ll instead stop, pause, and ask myself questions we ask in the program.”

As she’s found her calling through her work at RedRover, Minhhan’s primary motivation is to make a difference for future generations:

“I want to be there for the kids. I want children to grow up seeing less animal abuse in the world, less cases of domestic violence, less puppy mills. I want to read animal books to them and ask open-ended questions and see their eyes light up and see them get to this point of realizing things from the perspective of their animals, enabling them to have conversations about the treatment of their animals earlier on. Maybe kids don’t know what they can speak up about.

I want to give children the tools to be able to think on their own, to be able to be kinder, more compassionate on their own. Because, ultimately, it’s going to be their decision. We can only provide the tools and knowledge and stories and inspiration.

That’s why I’m here – because we have to start somewhere.”

Learn more about the RedRover Readers program >>