Leading with Empathy: Behind the Scenes with Devon

March 19th, 2021

By Helia Zarkhosh, RedRover Communications Coordinator

What does a typical day look like for RedRover staff members? How do we answer the call for help when people have nowhere else to turn? In our new series, “Leading with Empathy: Behind the Scenes at RedRover,” we share staff stories about our efforts to bring animals from crisis to care.

In this feature, Field Services and Outreach Coordinator Devon Krusko describes her recent deployment assisting the Humane Society of the United States and Humane Society International with the care of the remaining dogs from a South Korean dog meat farm rescue.

Field Services and Outreach Coordinator Devon Krusko with her rescue dog, Riggs

Imagine: 150 dogs arrive on trucks after a flight from South Korea. You’ve spent the better part of a week preparing for their arrival by creating temporary, spacious enclosures for each and every one of them complete with a cozy bed, wood shavings for added comfort, and food and water bowls. These dogs have been through unimaginable trauma. They’ve just completed a gruelling multi-leg journey. They’re tired, confused, and completely out of sorts. Maybe they’ve never been shown human kindness until now. Maybe they’ve never even been indoors. Whatever their story, you have one job: keep them safe and comfortable. That will mean different things to different animals, and Devon is astute at recognizing the needs of the individual. As she tells it:

“It’s just second nature going into these situations – I don’t make eye contact with the dogs, I really don’t speak to them. I read their body language, give them space, and interact with them where they’re at emotionally and mentally. It’s just about what I can do to make them as comfortable as they can be in my presence, which to them can be a really scary stranger as opposed to something comforting.”

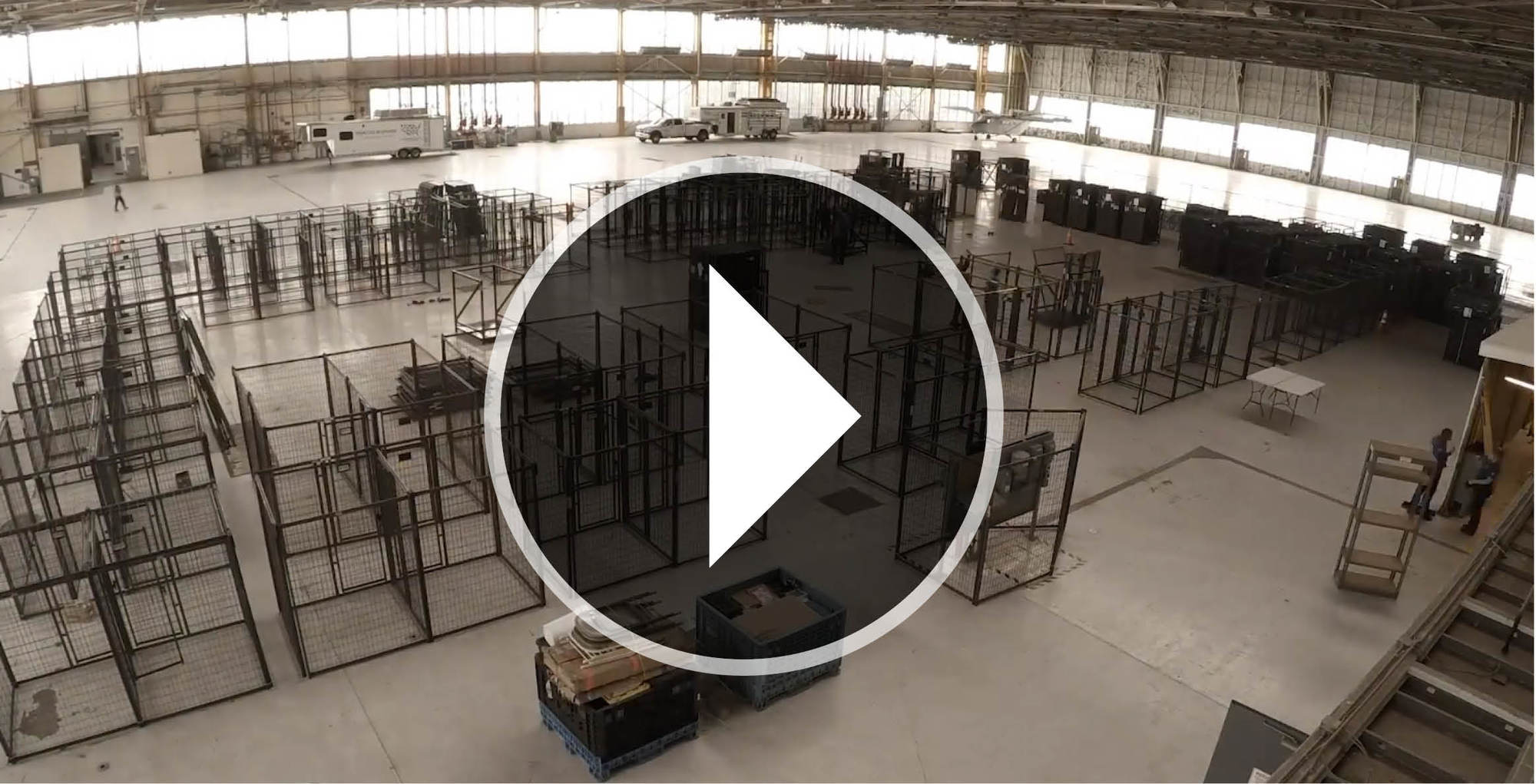

Watch: HSI’s temporary shelter built from the ground up

No matter the situation or the deployment, Devon considers the perspective of the animal, saying, “The situation that these dogs came from is a situation that they know. As difficult as it may be for us to imagine that situation, or however much neglect or cruelty was occurring, that’s actually the situation that they are most comfortable in or familiar with.”

Fighting our own impulses is part of the reality of working with animals in crisis. And it may seem counterintuitive – the urge is to show these animals love with pets and cuddles, to want to help them heal in the same way you’d comfort your own pet. But they’re not our pets, and giving them that kind of attention before they’re ready could actually be to their detriment. Devon is no stranger to the sentiment – so she focuses on doing what’s best for the animals and not what might feel good to her:

“I think we all probably have that urge. It’s hard to look at a cute little fluffy dog and not think, ‘Gosh, I would love to squish that little face or cuddle that friend.’ But with my background and training, I don’t think about them in that way. I hope that they reach that point someday, for them to have those comfortable relationships with people and enjoy the feeling of a good pet, but I think more so when you’re in it and get to see the dogs, and their behavior and body language, you wouldn’t want to try to force that on them because you can see how uncomfortable they are just with your presence.”

To help these dogs – especially the most severely undersocialized and uncomfortable ones — acclimate to their new world and prepare for a hopeful future as a beloved pet, HSUS staff carefully develop individualized training and behavior plans that all staff and volunteers must adhere to. A factor in any of these plans is to take things slow and steady in a safe environment:

To help these dogs – especially the most severely undersocialized and uncomfortable ones — acclimate to their new world and prepare for a hopeful future as a beloved pet, HSUS staff carefully develop individualized training and behavior plans that all staff and volunteers must adhere to. A factor in any of these plans is to take things slow and steady in a safe environment:

“Because their socialization is still a work in progress, these dogs are not in a place mentally or behaviorally where you can just leash them up and take them for a walk outside. That would be really traumatic and unsafe and super challenging. So what they’ve created is this really incredible space that’s secure, so it’s kind of like everyone has a tiny home in this ‘gated community’ and they can come out of their ‘tiny home’ which is actually a really large, double kennel space, and they can interact with each other for dog playgroups with novel toys, and novel people (like the volunteers), and then they’re also doing their behavior work with the staff. And it might look like something really small to an outsider but for the dogs, it’s huge.”

On this particular deployment, Devon had the opportunity to work with Gahee – a white, fluffy, “very squishable” pup. Devon recalls, “She’s very observant and is one of the dogs that would make you have that urge of ‘Gosh, I would love to just snuggle you and give you all the lovings.’” Thanks to patience and her specific training plan, Gahee started to become more comfortable around staff and volunteers. Devon describes watching her progress during this deployment:

“Part of [Gahee’s] behavior plan is just sitting near her with hotdogs in your hand and ignoring her while she’s out in her space. I had observed her doing that with the staff and I was asked to come in as a novel person to sit in there with her. It was a huge step for her because she came up to take hotdogs out of my hand. She also did some of her other behavior training which is when she’s taking that hot dog, you also touch her on the neck, so there’s some petting involved while she’s getting those yummy treats. That helps her to associate people and touching with good, positive experiences. She chose to use all of her enrichment time to stay with us and get pet, and enjoy those hotdogs as opposed to keeping away from us or playing with the toys or greeting the other dogs.

“And there’s something really special about the dogs who come from these situations when they do pick up those toys and you see them ‘dog’ for what may be the first time…they’re discovering that toys are really fun. There’s nothing like seeing a dog become a dog when they haven’t had the opportunity before.”

We recognize that we work in a field that puts us face-to-face with animals in crisis, and we sometimes see these animals at their worst point. That can look like a shut-down animal huddling in the corner, or their stress and fear is coming through growling and showing their teeth. Either way, we know we’re working with animals who are likely scared and uncomfortable. But we also get to experience a bit of magic when we see some light come back into an animal’s eyes: “I think on any deployment I go on, that progress can be made so quickly that sometimes the resilience of the animals coming from these situations is unbelievable. That never gets old no matter how many times you see it.”

Of course we hope for a “happily ever after” for each animal we work with. Devon reminds us that success might look different for different animals and stresses the importance of the individual, saying, “I think the greatest hope is that these dogs will be able to move on to the next chapter, whatever that may be for them. It’s probably unique to each of them. For Gahee, the next chapter could be allowing someone to put a collar and leash on her. That would be a huge milestone for her that shouldn’t be discounted. And then there’s finding that home that is willing to continue this work and offer [the animal] a really nice, loved life. And it may just look a little bit different to us, because even with years of work, you may still have dogs that are not what you typically think of when you think of having a dog.”